- Fictionalist.co

- Posts

- 5 Habits For Better Prose

5 Habits For Better Prose

How many of these good writing habits do you follow?

Last week, I asked a few author friends about the traits and habits that make for a great writer. Here are their top 5 prose-related habits. Do you do any of these? Let me know by replying to this email!

#1 use lots of sensory details

Great writers are evocative. Amateur writers often assume the reader can read his/her mind.

As a writer, you have a rich world inside your head, and it is your duty to transport the reader to this world. Unfortunately, amateur writers often fail at this duty. Why? Because an amateur writer isn’t thinking about the reader.

When I first started writing, the more vivid the scene was in my head, the less likely it was for me to describe it. I subconsciously assumed that if I can imagine a scene, so can the reader. As a beginner, I often described the irrelevant details (like the inside of a car and the texture of the seat) while neglecting the important details (like fact that the characters are driving at night).

Great writers treat description differently. They carefully use all five senses to paint a vivid scene for the reader, giving the reader enough context to understand the story. I call this the “Paint a picture” principle. (Mastering Fiction students will be familiar with it.)

But you don’t need to go overboard with the sensory details. You just need to provide enough context for the reader to understand the scene. Usually, one sentence for each of the four contextual cues is enough. There is no particular order you need to follow.

Who — paint the characters.

What — paint the activity the characters are doing.

When — paint the time, season, or year.

Where — paint the surroundings.

For example: “Mom and I sat across from each other. The power had just gone out for the night, but there was still enough dusk light to see the small plate of dumplings atop our grimy dining table. She nudged the plate towards me. Steam warmed my face. “Eat. I’m not hungry,” she whispered.”

#2 avoid repetitive words

Great writers are careful with their word choices. Amateur writers often repeat words out of convenience or laziness. While most readers won’t notice these repeats, those who do will have their immersion shattered.

Here is an example of a lazy repeat (from my own novel, after two rounds of editing):

“Her prints were washed away, and by the time I got to them, the sand was smooth again. I pressed my hind legs into the sand with force. Then, I stepped away and watched the next wave take it away.”

You see how I repeated the word “away” three times in close proximity? Read it out loud. It sounds like I don’t know any other words. Had I noticed this mistake, I could have easily written “I stepped back and watched my pawprint melt into the sea”.

Lazy repeats are hard to find. The best way to avoid them is by reading aloud. Our ears are sharper than our eyes when it comes to flow issues.

Alternatively, you can get your word processor to read your work out loud:

On Google Docs, select Tools in the menu. Select Accessibility. Check the box at the top for Turn on screen reader support. Press the OK button.

On Microsoft Word, click the Review tab and select Read Aloud.

On Scrivener, click the place you want to start reading, then go to Edit in the menu, select Speech, then click Start Speaking.

#3 avoid filtering

Great writers deliver the experience directly to the reader. Amateur writers filter it through the POV character.

Filtering is inserting the character between the reader and the experience, creating an unnecessary barrier. This means when a man jumps in front of the protagonist, the filtered description reads “he saw a man jump”. When the doorbell rings, it’s “she heard the doorbell”.

For example:

Filtered sentence: “She could feel the cold wind whipping her face.”

Unfiltered sentence: “The cold wind whipped her face.”

To avoid filtering, simply remind yourself to look for these filter words: saw, heard, felt, smelled, tasted, thought, believed, noticed, knew, observed, recognized, and discovered.

In most cases, you can fix a filtered sentence by removing the filter word and rewriting to put the focus on the experience instead of the character.

#4 avoid summarizing

Great writers let the reader form their own conclusions. Amateur writers spoil the action with thesis statements.

A thesis statement is a summary of what is about to happen, or what had already happened. This can rob readers of the opportunity to engage with the story on their own terms and diminish the impact of the narrative.

This is best illustrated with an example:

Summarized at the beginning: “Bobby was nervous for the performance. He clutched his guitar tightly as he sat in the sweltering spotlight. A thousand eyes judged him.”

Summarized at the end: “Bobby clutched his guitar tightly as he sat in the sweltering spotlight. A thousand eyes judged him. He was nervous for the performance.”

Not summarized: “Bobby clutched his guitar tightly as he sat in the sweltering spotlight. A thousand eyes judged him.”

Writers use thesis statements when they lack confidence in their storytelling abilities. As you become more experienced, you’ll slowly gain confidence in your skills and won’t need to summarize anymore. In the mean time, look for spoilers at the beginning and end of your paragraphs and chapters.

#5 use a consistent tense and point-of-view

Great writers are masters of tense and POV. Amateur writers hop between tenses and heads.

Tense-hopping is unintentional shift between past, present, and future tenses without a good reason. Often, this happens within the sentence, but sometimes tense-hopping spans entire paragraphs.

Head-hopping is the unintentional shift between point-of-view characters. This results in a sudden invasion into the mind of an unfamiliar character. It feels jarring for the reader, and makes your work feel amateurish.

Here’s a present-future tense hop:

Inconsistent tense: “She wakes up early every morning, makes herself a cup of coffee, and will go for a run before work.”

Consistent tense: “She wakes up early every morning, makes herself a cup of coffee, and goes for a run before work.”

Here’s a past-present tense hop:

Inconsistent tense: “She ran to catch the bus, but it leaves before she could reach it.”

Consistent tense: “She ran to catch the bus, but it left before she could reach it.”

And here’s a head hop:

Inconsistent POV: “John walked into the room towards Sarah, who sat by the window, deep in thought. He hoped she wasn’t still mad. She was thinking about the fight.”

Consistent POV: “John walked into the room towards Sarah, who sat by the window, scowling. He hoped she wasn’t still mad.”

The reason that the fragment “deep in thought” is a head hop is because John, the POV character, couldn’t have known that Sarah was deep in thought. John could only believe or assume she was deep in thought based on her behavior. Here, “looking pensive” also works. Or something more sensory, like “looking at the clouds”.

Avoid tense-hopping and head-hopping by being deliberate with your transitions. If you want to transition between tenses or POV characters, make sure to signal this clearly to the reader.

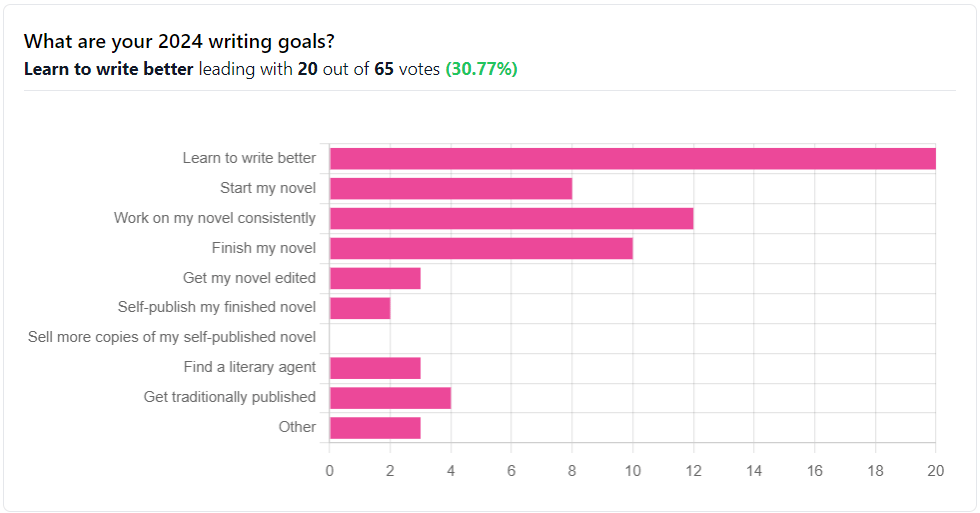

P.S. Here are the preliminary results of the writer’s survey!

Reply